Mr. Polidori, your photography often captures important moments of historical devastation – like the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina or Chernobyl – and turns it into art. Do you find misery beautiful?

I’m upfront about it: matter decays. Time goes on. It’s like learning to love the wrinkles in your face as you get older, you know? Everyone will age. You won’t look the way that you looked when you were young. But some people think it’s sinful to see beauty in that. A lot of beauty, the kind of beauty that those people like, I don’t find beautiful. They don’t relate to pathos because they have a problem with death. We all do to a degree – even me. But we live in a product society. We’re materialists! We deify man-made matter, and we want it to live forever. Insulting to me is this term that’s used, “ruin porn.” I guess by “pornography” they mean an unbridled, sinful, frolicking in destruction.

What would you call it?

My photos are physical graphic records. A lot of the places I’ve photographed simply won’t exist – many have already ceased to exist in the state that they were photographed in. They’ve been bulldozed over. Photography is collective memory – that’s its nature. It’s the physical world revealing its own self. In ten years or a century from now, when people have a different vantage point, they can look at the same photos and gather different data from it. It’s an aid of memory. I don’t make what’s known as abstract art; I am addressing phenomena in the real world.

Does that make it more meaningful?

This will be controversial, but for me abstract art is a lesser art because it’s, by nature, decorative. There’s nothing wrong with decoration, but it’s just not as deeply meaningful as iconographical art. I’m using pictorial forms to make comments about things in the real world, where decorative art is merely addressing the grammar of its own making. Whenever I take a picture, I have the audience in mind. I’m not ashamed of this.

So you’re not one of those artists that make art primarily for themselves.

I never liked those artists who say, “I make my art for myself, to please myself.” I don’t. I don’t do it to displease myself either, and I’m not making it to please the viewer but it is addressed to them. The purpose of my images is not to seduce someone, but I am interested in them looking at the subject, or perceiving the subject in a certain way. For lack of a better term: I’d like to change their minds!

One of your best-known works is a series of photographs you took in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, a place you lived for two years yourself. How did your memory guide you there?

This sounds dumb, but I kept looking for the houses where the bass player of my rock band lived, or my drummer’s house. I had some sentimental relation to it. I relived part of my teenage youth in a very different way. But it was really easy shooting in New Orleans. I didn’t have anybody saying no to me! When I shot in Chernobyl, I had government officials and Russians and Ukrainians bothering me. I found that more disturbing. The worst thing in New Orleans was trying not to get the car stuck in mud, and watching out for crazy, angry, wild dogs – I’m afraid of dogs. And I got lung infections from all the mold and stuff. But besides that, it was easy.

A lot of people criticized a photo that you took of a Hurricane Katrina victim who had died in her bed.

I don’t get the big deal with that! It’s a sin to photograph dead people? Hey, I didn’t kill her. I didn’t do it. She was just there.

It made me think of similar high-profile photos that have been accused of “vulturism,” like Frank Fournier’s photo of Omayra Sanchez or Kevin Carter’s photo of the starving toddler in Sudan.

There are certain kinds of criticisms that I might feel guilty about, but that’s not one of them. First of all, I didn’t go out looking for bodies. There was one, and it was transfixing to see it. And it’s not like I dragged out the body. I photographed the body the way that it was on the bed. I didn’t change anything. Give me a break. It’s all this kind of false morality stuff. I shoot a lot of places in slums in India and in Brazil and people say, “Oh, this is a kind of voyeurism, why aren’t you helping them?” What am I supposed to help those people with? I’m going to teach them to use large format cameras? That’s not going to help them in their life at all. I’m supposed to go and be some sort of missionary? No. To me, that’s an arrogant thing. I try to treat them with respect and dignity. I get their permission, and I try to not change their life at all. And I think this is the morally correct stance, and the politically correct stance to take.

Where do you draw the line when it comes to photographing destruction or atrocity?

I don’t think there’s a line. Why is there a line? Why? If you want to speak about Katrina, the aftermath… What can I say? All this internal dialogue, these understandable fears that we may have about death… Death is part of life. It has its place. It exists. I don’t see why it’s sinful to look at.

Are those things difficult for you to photograph?

When I shoot I don’t feel anything. I feel before and after, but I come with a pre-loaded gun. I just do the labors, the proper labors of doing it. I try not to feel too much.

Two years after Katrina, you infamously sold some photos to the Brazilian government for use in a campaign against smoking.

They wrote me emails begging me to use the pictures, they thought they had a certain psychological content, but still… I guess I shouldn’t have done that. I get so much crap for that.

Do you think that changes the original value of the photos?

But there is what I call literary meaning, which is of the now, and then there’s that kind of meta-history that I spoke of. The people in Brazil are relating to the meta-history of it. In Brazil, 9/11 never happened, Katrina is just a woman’s name. I don’t think it devalued those people. The residents of New Orleans 100 years from now will look at those pictures in a different way also. There’s a certain change that happens in historical perception when that occurs. And it doesn’t bother me.

Return to Top

Short Profile

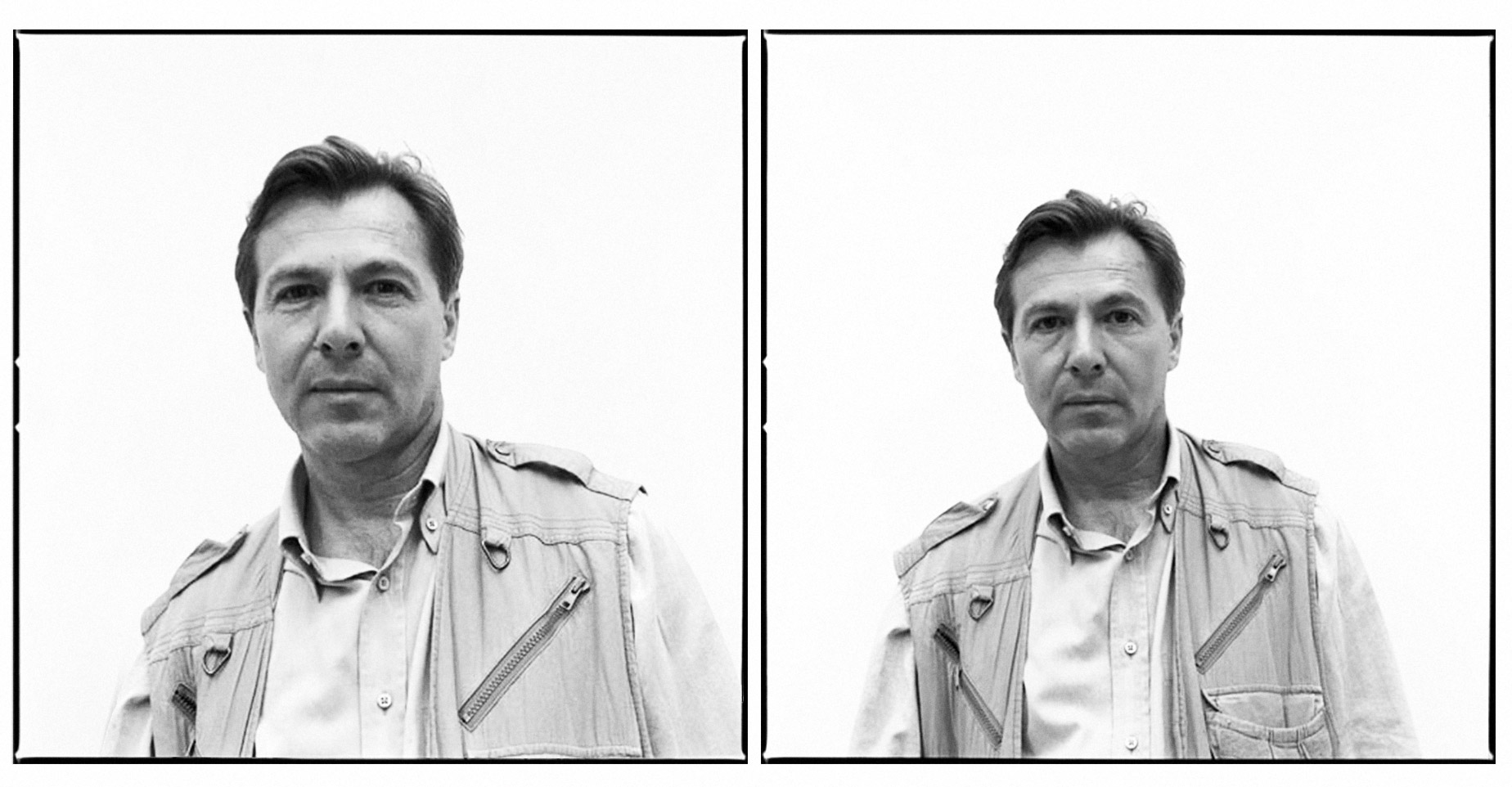

Name: Robert Polidori

DOB: 10 February 1964

Place of Birth: Montréal, Québec, Canada

Occupation: Photographer

Frankly, you have to be some kind of moron to say things like, “In Brazil, 9/11 never happened, Katrina is just a woman’s name.” But I suppose the Brazilian government is even more idiotic for buying photos from this “artist”.

Marcelo he is saying that people forget history especially when other countries did not experience the catastrophic event. They related to a picture for there own meaning and not from its origins. It became abstract art to them. You missed his point

And took his quote of context completely. Try harder Marcelo , you can do it.