Mr. Harris, satire is said to be the price politicians have to pay. What is the price you have to pay as an author?

Well, in De re publica Cicero wrote, “The worst rule of all would be government by clever poets.” I thought that was such a brilliant line! (Laughs) As a writer, I have to obviously go through a process of criticism, which can be painful. Often people don’t like your books — and they tell you. You’re judged by the public all the time, so in a sense that’s quite like politics. I don’t lose my job, though; I don’t lose my seat. But of course people stop buying my books and people stop being interested, so much like a politician, I’m dependent on public favor.

Many of your novels deal with political fiction, of course, but was it ever your wish to go into politics as a career?

No. I’ve really only ever wanted to be a writer.

You never even considered it?

Well, when I was a teenager I used to think about going into politics because I obviously liked it and I had beliefs and I enjoyed speaking and all that. But by the time I was 20 or 21, I knew that I wouldn’t do that. I’ve even been asked by The Labour Party and the Liberals in Britain in the past, but I’ve no desire to order people around and I don’t want to be ordered around by people. I don’t want to be responsible to anyone! Becoming a writer is all I could really do.

You once hinted that it’s impossible to not go slightly crazy if you’re in politics. Do you still believe that?

I think that a lot of people, if they stay at the top, almost invariably go crazy. The Americans are right: eight years is about all anyone can stand! After that, you know, there’s a very strong possibility you’ll be parting company with reality. (Laughs)

You touch on this in your writing as well. The difficulty of being moral while having power is often a theme in your novels.

The exercise of power inevitably involves compromise. It involves what some people would call hypocrisy or deceit. You can’t be a Boy Scout and rule a country, and I like that. That whole area of morality, practicality, and power is of endless interest to me.

I’m sure. You’ve explored this in almost every book you’ve written, whether it was based in Ancient Rome or World War II era Britain.

Well, it’s not really a matter of the period! It’s a matter of the story. I would set a story in any time, in any location, it’s just a matter of whether it’s of interest. That’s the way I work. I’m not comparing myself to him in terms of talent but I rather admire Stanley Kubrick, who would take his stories and set them in the Vietnam war, the First World War, the future. He’d do satire, he’d do Barry Lyndon… The period and everything, that’s not what’s important.

Have you always wanted to write historical fiction?

I came to novels almost by accident! I had an idea, a publisher said do it, I did it, and it was a completely unexpected success. I really had to give up my other job because it would have been crazy not to! It then took me three years to write a novel, then three years to write the novel after that, and then five years to the next.

Why did you need those years in between?

Writer’s block! I certainly had it on my second novel, Enigma. It was very painful and unpleasant. And I cured it by reading the letters of Raymond Chandler, who said at one point, “I cannot understand writers who complain about writing. Go and do something else! It’s the most fantastic thing to invent stories.” I read it and I thought, “He’s right! Why am I moaning and groaning and making a big thing of this? This is a pleasure.” The moment I did that, it was like I sort of relaxed into it

And that approach has lasted?

Oddly enough, yes. Now I’m much more eager to write. When I’m not writing a novel, I feel very bereft. And that’s a big change! I write more now than I did when I was a younger man and had more energy. I think in part it’s a function of growing old.

How so?

You feel no longer like the world is yours. Somehow you feel that another generation is taking it. And that’s fine. I sort of retreat into my own head a bit more. In there I’m not an old fool who has to have the zappers taken off of him and have the mobile phone explained to him and all that stuff. (Laughs)

To date your books have sold more than 12 million copies and you’ve been named columnist of the year. But could a successful, popular writer ever win the Nobel Prize?

No. If you’re popular, you’ve done a lot of the working out for people. And that means that you run the risk of appearing obvious. It’s quite hard to write popular fiction, but I can see that you cut out the middleman. It’s just you and the reader; there isn’t a priest between you to explain the text and tell people, “This is good for you.” The novelists I really like have never won the Nobel Prize. And a lot of completely awful, unreadable tosh wins the Nobel Prize! (Laughs)

I guess that’s not really the goal for you.

No. I am a populist, I believe in reaching an audience. The pretention that goes along with the literary novel, the deliberate obscurity — I can’t stand that. One writes for readers, not for prize committees or reviewers. I think that there’s also a deserved sense that if you’re popular then you’ve got your reward. The prizes are there to reward people and tell people about other novelists who aren’t getting the break, and I think that’s fair.

Since the Nobel Prize seems out of the picture, what else are you hoping to achieve in your career?

I have an audience, people know my books, people come up and they’ve got my books going all the way back to Fatherland. It’s very touching to see that. Without being pious about it, that is the reward. I’ve been very lucky — I took the risk to do the things that interested me, so I could have no possible complaints. There’s nothing else I could ask for, really, and if I drop dead tomorrow, I would have had a terrific time.

Return to Top

Short Profile

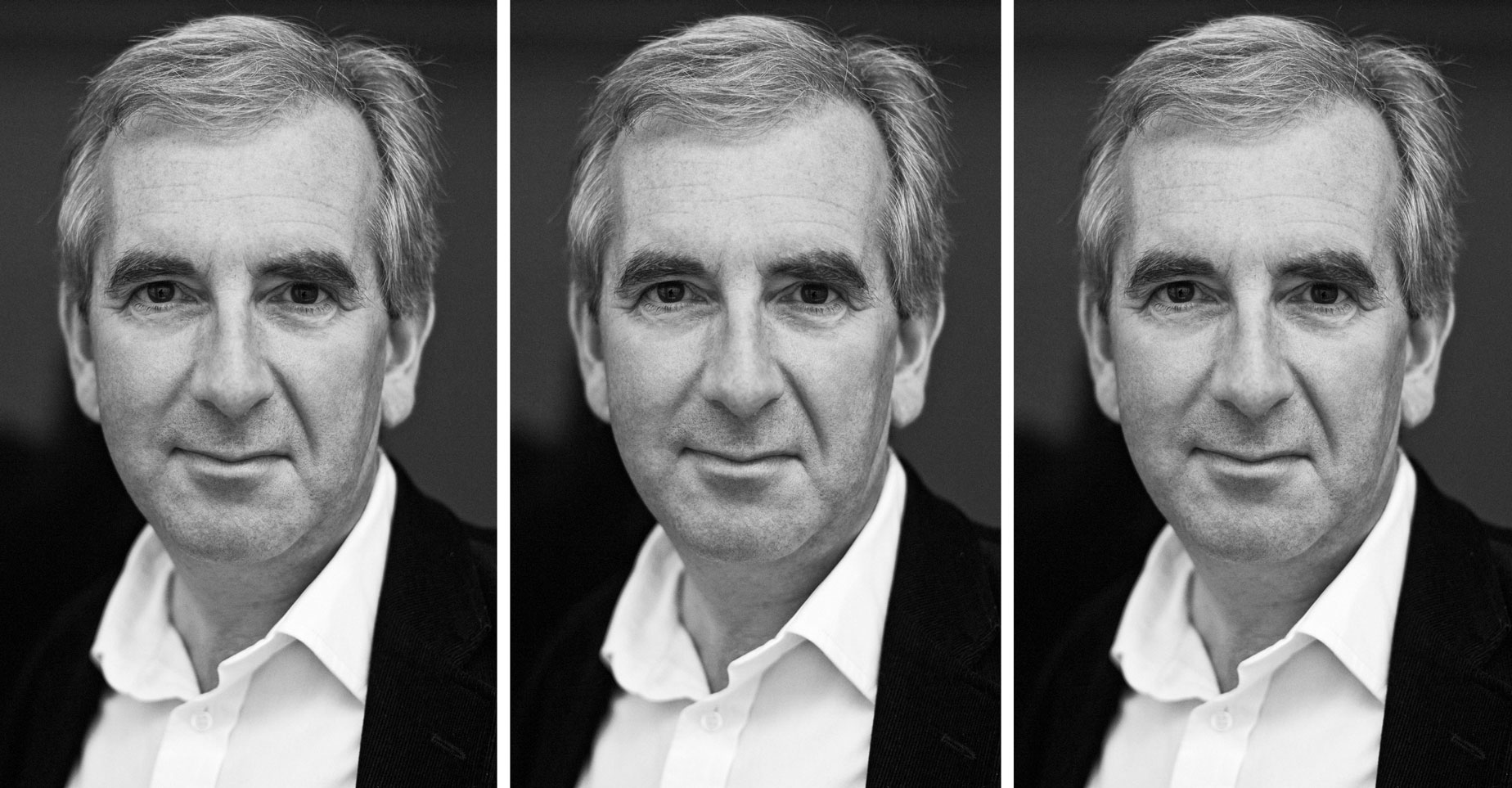

Name: Robert HarrisDOB: 7 March 1957

Place of birth: Nottingham, United Kingdom

Occupation: Author

Robert Harris' new book, Dictator, was published internationally by Hutchinson & Co., and by Heyne Verlag in Germany.

Comments

write a comment, read comments