Mr. Deacon, how do you see your work as a descendent of the tradition of sculpture?

I am interested in carving, I am interested in modeling, but when I left art school I found that, curiously, I didn’t really know much about the history of sculpture, so I set about learning about the history of sculpture and when I first started teaching I did run courses on the history of sculpture for sculpture students. I thought that they were very badly served by history art departments.

Why, what do they teach?

Mostly they taught the history of painting and I thought you could discuss sculpture in a different way. I thought you could discuss the history of the twentieth century when sculpture-making suddenly comes from the background to the foreground and became a very important driver for a lot of the developments for the art of the twentieth century. Contemporary art really owes a lot to sculpture-making.

When you first started out you called yourself a fabricator rather than a sculptor. Would you still say that?

When I said that about being a fabricator I was quite young and it was an obvious observation about that fact that most of what I did was put together rather than carved or modeled. I also quite liked the double sense of fabrication in English: it can be a construction as well as an imagined event. I also think that it had a bit to do with the way that a young artist is looking for some kind of space, a theoretical or conceptual space in which to make work. So I was trying to define a certain kind of potential space for me to be able to work in.

Was that process similar to “finding your voice” as an artist?

Yeah, and it was also a way to explain it. You find an adequate story that enables you to continue doing stuff, a good enough explanation for you to keep going. If you don’t really have an explanation, then it is quite hard to keep on at it.

Did you ever struggle finding a reason for doing what you do?

I have had depressed moments and periods when it was difficult. I started making sculpture when I was really quite young, when I was thirteen or so, and for a long time it was very straightforward – I just sat down and I knew what to do. And then for various reasons after graduating from art school, partly to do with the work, partly to do with things that were happening in my life, partly to do with the shock of being ejected from this cozy world of support, it was difficult to continue.

Were you ever truly depressed?

Not deeply depressed, but not knowing what it is you’re doing and why you’re doing it, not knowing why you have to get up in the morning and not knowing where the future is. It took maybe another six years. I went back to art school and did post-graduate work and I’d include those post-graduate years as part of that kind of reconstruction process. Since then there have been periods, but nothing on the same scale.

When did you become confident that what you were doing is valuable?

It is not that I saw it was valuable, more that I realized that I didn’t want to stop. So there was no economic value attached to it and in fact it was financially very difficult – but by then I knew I wasn’t going to stop. Whether I kept it up as just an evening hobby was another question, but it was a part of my life that I wasn’t going to give up. And I was a more pleasant person for doing it.

Is that the difference between a work of yours and a piece of interior design – the motivation?

Well, I think there is a difference between being asked to do something and just doing it because you are interested in doing it. From time to time I am asked to do something too, but I think there is a difficulty for artists when you make a lot of work for exhibitions and then after the exhibition you don’t know why you are making work anymore. In the ’90s I changed things around and rather than making work for exhibitions, I wanted to have a stock and make exhibitions based from that stock so there was more continuity. I wanted to try to eliminate some of the ups and downs.

How long does it take for you to fully develop an idea?

There is a big steel work I did recently that took six years. Another big wooden work was a very quick process due to necessity because we had a very specific deadline and I had the idea very quickly after seeing the space for it. That was a nine-month process.

I’ve heard that Alfred Hitchcock didn’t enjoy shooting his films because for him the exciting part was the idea. The execution was boring. Is that the same for you, if making a piece can take up to six years to make?

It doesn’t really work like that for me. There is a moment in the middle when it is always quite slow-going because you are just making stuff, but the end is always exciting. You can make quite radical decisions in the end, turn things upside down. I have sometimes made up a lot of components – twists, bends, and all that – and then assembled them, which puts another stage into the making process. You don’t need to have an idea, you just need to think, “I like this, I like that…”

Your work is inspired by a wide variety of things – from a piece of cardboard to the head of a Marge Simpson doll. Does inspiration occur to you all the time?

It doesn’t happen all the time, but you have to be able to not dismiss stuff because it’s banal. It is a bit of a blessing to actually have ideas pop in and they don’t have to come shining, they can come from really casual encounters. In a way you could pick up any bit of trash and apply a sort of investigative mentality to it and derive interest from it.

Was it a long process to cultivate that ability or did it come naturally for you?

I think that is quite natural, the way I look at it. I did have a fantasy museum as a boy where I picked up shards or bits and pieces, a bit like a cabinet of curiosities. But not to distinguish between the intended and the unintended was always there. I didn’t differentiate them from the beginning.

Is that what your art is about – looking for connections between shapes and forms in order to find balance?

I think that is a part of the way we look at things anyway, isn’t it? We try to connect things together. What the art does is it allows you to do that, but it doesn’t actually fully explain itself. You can come at it with a different route another time. You get taken off to connect things together, but somehow the materiality of the work always brought you back to a point that you could go off from in a different direction. So the materiality is a kind of a reality or kind of a stop, but not a finish.

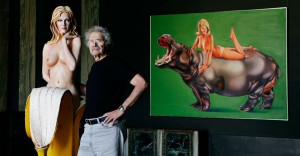

Short Profile

Name: Richard DeaconDOB: 15 August 1949

Place of Birth: Bangor, Gwynedd, Wales

Occupation: Sculptor

Comments

write a comment, read comments